Video interview at the bottom.

Video interview at the bottom.

Yes, it’s true. Krishna Das went to prison for Call and Response. The Call and Response Foundation, that is.

For the least few years, the nonprofit foundation has been arranging for kirtan wallahs to chant in prisons, psychiatric facilities, children’s hospitals, and other places where people might benefit from the healing power of mantra music. This time, it was the Chant Master himself serving a little time in prison.

(You can support this important seva by contributing now to the Call and Response Foundation’s Prison Outreach Program.)

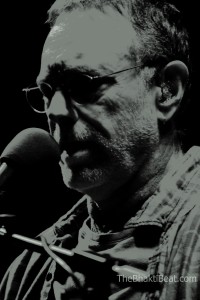

It was a gray, frigid Monday afternoon in northern Vermont, vexed by a drizzling rain that threatened to turn to snow. Krishna Das and his drummer, Arjun Bruggeman, arrived at the Chittenden County Regional Correctional Facility for Women early, after a double-header weekend of kirtan+ workshop that were partial benefits for Call and Response.

They were at the medium-security prison in South Burlington to fulfill the pie-in-the-sky request of an inmate named Lucinda. Six months earlier, Lucinda had picked up a Krishna Das CD in the prison library. Apparently, she couldn’t get enough of it, and she wondered aloud to her counselor, Philip Pezeshki, if Krishna Das would come chant with them. Long story short, here he was.

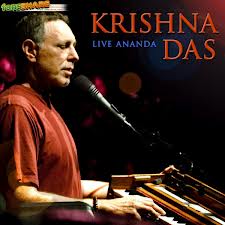

They brought nothing but a harmonium and a Naal drum.

They brought nothing but a harmonium and a Naal drum.

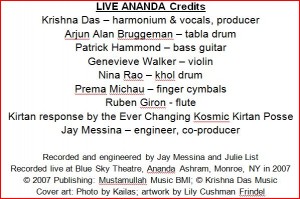

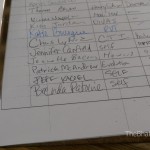

Bruggeman’s usual tablas were left behind because the little metal hammer that he uses to tune them was a security risk. The six of us — including C&RF director Jen Canfield and local wallahs Patrick (Yogi P) McAndrew and Jeanette Bacevius — dutifully stashed wallets and cell phones and jackets and scarves that could present a choking hazard into the lockers in the waiting room, then traded our driver’s licenses for visitor’s passes. Krishna Das and Arjun opened up their instruments for a thorough search by a serious but pleasant enough security guard. I presented my Nikon to the guard, hoping for a miracle, but it was not to be, so I reluctantly stuffed it into the locker with everything else. At least he let me keep my little reporter’s notebook (after leafing through it thoroughly) and a pen to take notes. Then we all took off our shoes and filed through a metal detector, their instruments and my notebook set to the side.

We were led through a series of security doors to a windowless, concrete-block room off a main corridor. There was a whiteboard with a hand-written list of stress-relief strategies on one wall, and on another wall, a single poster exhorting viewers to “end the silence” about sexual abuse. A few rows of yoga mats, folded in thirds, were set up in a semi-circle, with a row of mismatched chairs at the back.

KD and Arjun set up their instruments underneath the “End the Silence” poster. Then KD wrote out the words to five chants on an easel. Shree Ram Jay Ram Jay Jay Ram. Om Na-moh Bhag a vah tay Na ma ha. Om Na-mah Shee vy ah. Jay a Jagat Ambay. Om Ay-eem Shreem Sara swa ty yay Na ma ha.

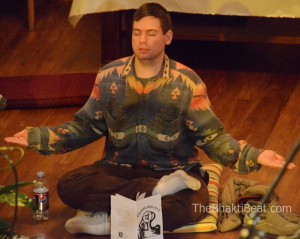

Lucinda, the inmate responsible for all of us being there, came in and sat with KD for several minutes to interview him for the prison newsletter. Soon enough, about a dozen or so inmates — most appearing to be under 30 — began filtering into the room. They looked somewhat bewildered, even gruff, like they didn’t know what they were getting into. Several prison staff members also came in, with serious faces. Honestly it was hard to tell who the inmates were, until I realized they each had on a dark blue scrub shirt over their street clothes. The chairs in the back filled up quickly, and the seats in the front, closest to where KD and Arjun were now seated cross-legged on yoga blocks, remained empty.

Lucinda, the inmate responsible for all of us being there, came in and sat with KD for several minutes to interview him for the prison newsletter. Soon enough, about a dozen or so inmates — most appearing to be under 30 — began filtering into the room. They looked somewhat bewildered, even gruff, like they didn’t know what they were getting into. Several prison staff members also came in, with serious faces. Honestly it was hard to tell who the inmates were, until I realized they each had on a dark blue scrub shirt over their street clothes. The chairs in the back filled up quickly, and the seats in the front, closest to where KD and Arjun were now seated cross-legged on yoga blocks, remained empty.

No, this was not going to be your average Krishna Das kirtan.

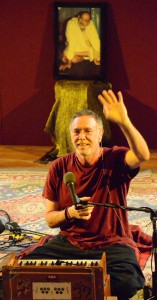

KD started by telling the group what kirtan was not. “This is not a religious practice. There is no blind faith required,” he said. “This is not a missionary trip. I’m here because I was invited.”

(In the waiting room, KD had told me that the last time he chanted in a prison, it was with a group of 100 or so men in a maximum-security facility in the South. “Everything was going along great,” he recalled, “until I started singing the Maha Mantra.” As soon as the prisoners heard Hare Krishna, they started scowling and fidgeting, looking at one another and shaking their heads. Every one of them got up and walked out. Every. Single. One. He hadn’t been back to a prison since.)

(In the waiting room, KD had told me that the last time he chanted in a prison, it was with a group of 100 or so men in a maximum-security facility in the South. “Everything was going along great,” he recalled, “until I started singing the Maha Mantra.” As soon as the prisoners heard Hare Krishna, they started scowling and fidgeting, looking at one another and shaking their heads. Every one of them got up and walked out. Every. Single. One. He hadn’t been back to a prison since.)

Kirtan, Krishna Das told those gathered in the cold cement room, was “a way to quiet the mind, to kind of short-circuit the stories we tell ourselves.”

“We mostly don’t get a vote about our thoughts,” he said. “Chanting is a means of winding down the mind and training ourselves to let go of thoughts.”

He initiated the singing as he always does, with an opening prayer, which he described as “a prayer to that place within us that is looking for true love.” After the prayer, he paused in the silence of the room, a silence that was routinely interrupted by a loud slam of the security doors in the hallway outside. Looking out at the women prisoners in the back, he said quietly: “These mantras are sounds that have a magnetism to them. By repeating these mantras, we bring the mind to a quiet place. When the mind is quiet and the heart is at peace, your life can take a different course.”

Sri Ram Jai Ram Jai Jai Ram…

And so it went. Not unlike a typical Krishna Das workshop. Talk a little. Chant a little. Talk a little more. Chant a little more. Yet this one was verrrrry different. We were reminded of that about halfway into the session. KD had just finished saying something about how to “find some peace no matter what the outside world was throwing at us” when a beefy security guard pushed through the door loudly, with a list in his hand. KD stopped talking and simply said: “Come on in.” The guard peered around the room, unsmiling, checking people off his list. He called out a few names — not the Names that had been ringing in the room a few moments before, needless to say. Then with a slam of the door, he was gone.

“We’re all still here,” KD joked self-consciously, with an awkward chuckle. Then he picked up the thread, saying there were all kinds of practices — chanting among them — that one could use to “find a way to chill yourself out no matter what’s going on.” It was an appropriate lesson for the moment, and you could feel it resonating with the folks seated in the room.

A couple times during the session, Krishna Das asked if anyone had questions. It wasn’t until the end that one woman spoke up, asking him if he had always known that this is what he would do. He told a story he has told many times — of how devastated he was when his guru Neem Karoli Baba (Maharaji) told him to go back home to America; how he had asked Maharaji: “How can I serve you in America?” and Maharaji laughed at him with a look “like he had just bitten a sour pickle;” how he, Krishna Das, was walking across the ashram’s courtyard later on and was suddenly struck by the answer: “I’ll sing for you.” That was 1973, KD said. It took him 21 years, until 1994, to finally start singing.

A couple times during the session, Krishna Das asked if anyone had questions. It wasn’t until the end that one woman spoke up, asking him if he had always known that this is what he would do. He told a story he has told many times — of how devastated he was when his guru Neem Karoli Baba (Maharaji) told him to go back home to America; how he had asked Maharaji: “How can I serve you in America?” and Maharaji laughed at him with a look “like he had just bitten a sour pickle;” how he, Krishna Das, was walking across the ashram’s courtyard later on and was suddenly struck by the answer: “I’ll sing for you.” That was 1973, KD said. It took him 21 years, until 1994, to finally start singing.

Then he told the inmates a story I had never heard. He said he didn’t think they were even going to let him into the jail for today’s session because he was a convicted felon. Say what? Yep, Krishna Das told us he had been charged with money laundering after a criminal investigation involving the IRS and the FBI. He told the group that it was an “insane story” that they would never believe. One woman replied, “Oh yes we will,” and they all laughed. So he related how he thought he was going to end up in prison, but instead — due to a somewhat remarkable series of graces involving the judge, prosecutor and parole officer in the case — was sentenced to six months of house arrest. He spoke of the period as a blessing, a relief, a much-needed opportunity for rest after a grueling tour schedule.

More importantly, he said, “Being convicted freed me from the secrets of my past. Now everybody knew. I didn’t have to hide it anymore.”

When there was only time for one more chant, Lucinda, the inmate responsible for KD being there, requested ‘Amazing Grace’ with the Maha Mantra. I held my breath, remembering KD’s story about all the men walking out when he started singing Hare Krishna. “We cooooould,” KD replied hesitantly… “Let’s sing the third one,” he deflected, pointing to the whiteboard where the chants were written out phonetically.

When there was only time for one more chant, Lucinda, the inmate responsible for KD being there, requested ‘Amazing Grace’ with the Maha Mantra. I held my breath, remembering KD’s story about all the men walking out when he started singing Hare Krishna. “We cooooould,” KD replied hesitantly… “Let’s sing the third one,” he deflected, pointing to the whiteboard where the chants were written out phonetically.

Om Namah Shivayah.

A long silence — blessedly uninterrupted by doors slamming — followed. Then KD looked out at the women and said simply: “Take good care of yourselves, okay?”

Afterward, many of the inmates lined up to thank him, to shake his hand or receive a hug. Most were new to chanting. One woman, Chelsea, said she found the session to be “really inspiring and cleansing.” She told us she felt energized, and definitely wanted to chant again. Another, Sarah, confessed that at first she thought it was “a little weird,” but by the end, felt that “it really worked. I absolutely loved it.” Adrienne said she felt relieved: “The stress is gone. I’m more relaxed. I hope he comes back.” A group of them milled around, smiling, chatting, not wanting to leave. Somehow, the cold concrete room was warmer, softer…

“Come back every week!” a young blond inmate named Suzi exhorted KD.

When all the staff and inmates were gone, our little group walked back down the hallway and through the double security doors . We gathered our belongings, traded our visitor’s passes back for licenses, and bundled up to face the frigid Vermont evening. Outside, a cold rain was still falling, and darkness had descended. None of us seemed to notice.

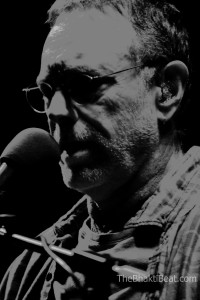

Before we disbursed, Krishna Das agreed to a short video interview outside the prison door. I dare you to not be moved by what happens midway through it…

“Everybody’s a prisoner, sweetheart. Prisoners of our own minds.”

Support the Call and Response Foundation’s Prison Outreach Program here.

View the Photo Journals of Krishna Das’ prison visit in Vermont 2014, and his kirtan and workshop, on The Bhakti Beat facebook page.

Connect with The Bhakti Beat!

Subscribe to The Bhakti Beat

The Bhakti Beat on facebook

The Bhakti Beat on twitter

The Bhakti Beat on YouTube

The Bhakti Beat on Google+

Like what you see here? Help us keep The Bhakti Beat flowing! Consider donating today, a one-time contribution or a recurring contribution — any amount is so appreciated and will help us continue to bring you the bhav. The Bhakti Beat is a labor of love, completely self-funded by Brenda Patoine (moi), who is a freelance neuroscience writer by day. Every bit helps! THANK YOU! Donate Here.

Mark this day in bhakti history. White Sun, the Los Angeles-based Sikh-tradition mantra-music band, has won The Grammy for Best New Age Album. This is the first Grammy for any artist in the sacred chant/kirtan/bhakti/mantra-music genres of music.

Mark this day in bhakti history. White Sun, the Los Angeles-based Sikh-tradition mantra-music band, has won The Grammy for Best New Age Album. This is the first Grammy for any artist in the sacred chant/kirtan/bhakti/mantra-music genres of music.